By: Michael Druffel

The Chase–First Day

My first grad school trip to the archives ended in defeat. I had made an appointment to visit the Berg Collection at NYPL to investigate material on Mark Twain. Because I hope to produce a paper on how the material of publishing influenced Twain’s literary content in Huck Finn I had hoped to see Twain’s letters to his publishers, as well as letters to the illustrator, EW Kemble, and any relevant material the archivists could suggest. While corresponding with one of the helpful, friendly, and knowledgable archivists I had been warned that some of the Twain material was out for digitization (a process I heartily support). Optimistically I reasoned that it would still be a good experience to learn about a) the Berg Collection in general, b) whatever material was in house, and c) new search terms to use in my further research that might come from working with the archivists or the Berg’s indexes. Besides, a visit to NYPL would barely be out of my way.

Points a and c were fulfilled wonderfully, and I’d like to touch on them in a minute. However, when I arrived at the Berg I learned that I had been way too optimistic about the material that remained. The Berg had sent pretty much all the Clemens manuscripts, letters, and notes to be digitized. If it was produced during Twain’s life time, it wasn’t at the Collection. The material was due back, according to one archivist, in September (2014), but likely wouldn’t be expected until February (2015) at the earliest. This certainly got me thinking that if I were writing a book, a serious, for-tenure book, then it would probably be a good idea to call around to different archives while I’m still coming up with the topic for the book to learn what is or isn’t available. Deciding on a topic and finding that material is out for at least 1/2 year (and that’s only how long the material was overdue for) could damn a project. I’d be curious to hear if anyone has stories of this happening before, or if I’m playing Chicken Little w/r/t the deleterious impact of lacking archival access. Either way, it’s a lesson at least for seminar papers, which obviously can’t afford 1/2 year of archival absence (if that was conceived of as being important to the project).

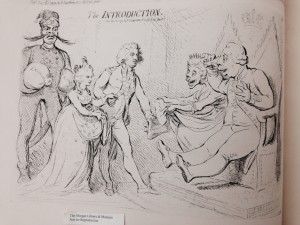

However, the trip was not wholly unprofitable. I have my NYPL Berg Collection reader’s card. I know how to submit call slips to call up books in the Berg. And I introduced myself to the Berg’s friendly and helpful staff. But I also did gain some more search terms and knowledge for my paper on Twain. While the material produced during Twain’s life was almost wholly absent from the Berg, the collection had some rare books on Twain that helped me. Two in particular were Arthur Vogelback’s 1939 PhD thesis The Reception of Huckleberry Finn in America and a collection of Century magazines from the 19th century reprinted in a bound volume. While Vogelback’s thesis was old, it was thoroughly researched. He had combed newspapers from the 19th century to offer a wide variety of perspectives on Huck. He made the interesting point that journals, magazines, and papers from Concord were the most critical of HF and were some of the first to call for its ban. Vogelback argued this was because Mark Twain had said some less than flattering words about the Sage of Concord. (Apparently, in a speech Twain called Emerson “bogus.”) Vogelback’s book also alerted me to a truly strange incident involving Huck in which an artist had drawn an erection or penis (the image is really so crude that it’s hard to tell what the thing is, or even if is an innocent mistake and the imaginative viewer projects the phallic meaning onto it) on Uncle Silas in one of HF‘s many pictures. When the offending image was detected the books hither to sold were recalled and reprinting was further delayed.

Overall, Vogelback’s thesis pointed to a struggle between Twain and the papers who were quick to mock the illustration boner, call for censorship of Huck , and deride the subscription model Twain used. The rift between Twain and some papers has many causes (the aforementioned Emerson slight), but one of them seems to be advertising money. Some newspapers seemed to think Twain didn’t pay enough for ads and were ready to take his work to task as a result. Even though I didn’t see any primary documents, it was helpful to learn how the relationship between press and author shapes the perception of the book.

The other interesting book I found was the Century volume. One of issues inclosed had the famous feud chapter from HF printed as a kind of teaser for the rest of the book. While it didn’t shine anything new on the process, it gave me a good idea of how Twain did use magazines for advertisement. The excerpt included five of EW Kemble’s illustrations as well, which shows, I think, that a big reason for buying books in the 19th century was the art that came with them. (Twain’s letters to his publishers, which I found in an edited volume by Hamlin Hill confirm this.)

While the trip wasn’t a rousing success, I think there were points I could take away. However, since I didn’t get to handle any primary documents, I made a second trip to another archive: NYU’s.

The Chase–Second Day

Feeling like it would be good to handle primary documents, instead of the still helpful books I found in NYPL, I used ArchiveGrid to find another archive nearby. This time I located one that held two letters from William James. Since I am in a class on Pragmatism, I thought it could be useful to check it out. This archive was at NYU, and having applied for a MaRLi, but yet to redeem it at NYU it was a good experience to get there, get the card, and visit the archive.

The WJ material was scant. There were two letters written in sloppy handwriting asking for copies of his book to sent to people. They were in the Helena Born collection, a single box for material created (donated?) by Helena Born, who is, as far as I can tell, an American socialist. I must admit that the visit did nothing to further my project, but it was not w/o merit.

Perhaps the most useful thing I learned was that NYU seems to have great socialist, Marxist, and labor material. These are all topics that interest me, so I’m sure I’ll be back to the archives sooner than later. I’d also recommend to anyone else dealing with labor to check them out: NYU’s Tamimant Library in particular, which is in the Bobst main library building (10th floor) by Washington Park.

But the most fun I had in the library was finding a watermark. I attended after hearing Steve Jones talk so I was feeling for lines and watermarks in the paper. One of the WJ letters had a mark visible when held to the light that read: “Royal Scot Linen / WB Clark & Co / Boston.” It was a lot of fun to see it there and know how it got there.

While neither archival visit furnished me with a perfect document, I think that it was good to get more info for my Twain paper, and fun to see Steve Jones’s facts in action. However, I decided against visiting a third archive to find a really great primary document. Two was enough for this project I thought.