By: Erin Glass

Below are a list of sources that are helping me think through Social Paper (SP), a software platform I’m working on with the Digital Fellows. Essentially, we aim to build a free, open source socialized writing environment that will enable students to easily share, manage, track and “socialize” the entirety of their writing across their graduate school career. There are several key aspects that differentiate SP from current methods and tools. 1) Instead of distributing and producing writing across multiple “siloed” channels (class blogs, seminar papers, etc) which inhibit a coherent perspective (as well as efficient control) of one’s developing body of work, all student writing will “live” on the student’s online workspace. For every piece of writing, the student will determine whether it is associated with a class, topic, working group, so that relevant peers may be notified of their work. 2) For every piece of writing, the student will have full control of the level of publicity. Students may choose to share the work only with a select group, such as a class, a few trusted peers, a professor, or alternately, may choose to have their work completely public. 3) Like Google Docs, the tool will allow for peer commenting and discussion in the margins, but unlike Google Docs and other free commercial tools, students can rest easy that their content will not be mined for corporate use. 4) The activity generated on SP — from the submission of writing to the commenting on peers papers — will be surfaced (according to the student’s privacy settings) through personalized activity streams with the hope of raising awareness in the student community of the work being produced by their peers.

This theoretical motivations driving the development of this tool draw on two bodies of research: 1) the social production of knowledge 2) a critique of technocapitalism as it relates to the tools, methods, culture of practice, and law used to carry out scholarly communication (though I will emphasize that we should extend our thinking of scholarly communication to include the transmission of knowledge among students, not just professional academics).

Bowers, C. A. The False Promises of the Digital Revolution. How Computers Transform Education, Work, and International Development in Ways That Undermine an Ecologically Sustainable Future. New York: Peter Lang, 2014. Print.

Bowers writes on education, ecojustice and the commons. His work is important to me as it offers a critical perspective on the development of digital technologies and their social consequence. In this work he argues that while digital technologies have rapidly improved our ability to generate and communicate knowledge, they have also contributed to the “individually-centered form of consciousness” which is “unable to grasp the short- and long-term consequences” of the environmental degradation taking place. Bowers demonstrates the “myths, misconceptions, and silences” inherited in language that have contributed to a hubristic, placeless rhetoric of technological progress that woefully, if not willfully, misunderstands the true challenges at hand. Though this work is not about scholarly communications in itself, it is important in its dramatic reframing of the stakes of education and, in a post-McLuhanian manner, provides useful analysis for understanding the impact of digital technologies on the production, possibility, and meaningfulness of human thought.

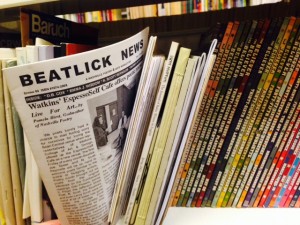

Dewey, Anne Day, and Libbie Rifkin. Among Friends: Engendering the Social Site of Poetry. Print.

This collection of essays examines the social production of postwar American poetry, primarily through the theorization of “friendship” as a fertile, though not always unconflicted, site of creativity. The topics presented here range from letter correspondences, small literary magazines, collaborative poetry writing, literary communities and radical collectivities working in the digital age. I’m interested in this work, as well as Dewey’s work on the construction of public voice in Black Mountain Poetry, for its tracing the various modes of friendship, community and intellectual exchange that contribute to creative productivity.

Drucker, Johanna. Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard U, 2014. Print.

Drucker writes about the history of graphic design and digital humanities. In this work, Drucker provides a “visual epistemology,” or principles for analyzing graphical user interfaces (GUIs) to help us understand how interfaces mediate the user’s interaction and knowledge production. Drucker’s historical analysis of the “screen,” is critical for exposing the non-neutrality of GUIs today. Combining Drucker’s visual epistemology with Bower’s critique of the “individually-centered” form of consciousness reinforced by digital technologies, how might we imagine new GUIs that would better emphasize the social role of knowledge production?

Elbow, Peter. Writing without Teachers. New York: Oxford UP, 1973. Print.

Elbow is known for his work in composition studies, particularly his theorization of the writing process as outlined in this now classic work. Here he observes that writing for peer review can significantly enhance a student’s growth — not to mention their excitement — in writing. Elbow’s emphasis on the benefit of a social environment to share one’s writing and feedback is one of the key motivations of building Social Paper.

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy. New York: New York UP, 2011. Print.

Now the Director of Scholarly Communications at the Modern Language Association, Fitzpatrick writes about the challenges and opportunities facing the publishing scholar in the changing landscape of academic publishing. Drafts of this work were first presented online through CommentPress, a free and open source software component which enables users to comment on paragraphs of long form texts, making the work both a theoretical and performative exploration in new models for peer review in academic publishing. Though this work focuses on peer review, and other issues of scholarly publication, as related to professional academic, the tools, practices, and critiques are applicable to questions concerning communication among students.

Illich, Ivan. Tools for Conviviality. 1975. Print.

Ivan Illich offers an anarchist’s critique of education and the tools and practices used to carry it out. In Deschooling Society, he writes, “The current search for new educational funnels must be reversed into the search for their institutional inverse: educational webs which heighten the opportunity for each one to transform each moment of his living into one of learning, sharing, and caring.” Though I have not yet read Tools for Conviviality, I’m hoping it explores this theme in greater depth, as a means of thinking through how we can better shape our platforms of knowledge transmission to cultivate “learning, sharing, and caring.”

Lovink, Geert, and Miriam Rasch. Unlike Us Reader: Social Media Monopolies and Their Alternatives. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2013. Print.

Though I have yet to read this reader (freely available on the web through Network Cultures) I’m excited by the prospect of a series of contemporary essays that directly attempt to theorize and critique the social media phenomenon. The essays here discuss a wide range of topics related to social media — such as privacy, labor, rhetoric, affect, and political movements — which are critical to think through when formally integrating a social media structure into the production of graduate student writing.

Stallman, Richard. Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays of Richard M. Stallman. Boston, MA: Free Software Foundation, 2002. Print.

Richard Stallman is a computer programmer and free software activist. Stallman is a fierce supporter of privacy rights and Free Software. Stallman coined the term, and started the Free Software Movement, as a means to fight the restrictions built into proprietary software which domesticate and manipulate the user for corporate gain. Though Stallman is a controversial figure, he is useful in thinking about how subtle restrictions in software can give corporations and political entities vast power over the civic body, not only through surveillance but though the user’s learned passivity. In these essays, Stallman defines Free Software and argues why it is worth fighting (and programming) for.

Taylor, Astra. The People’s Platform: And Other Digital Delusions. New York: Metropolitan, 2014. Print.

Taylor here critiques the premise that “the digital transformation” is a “great cultural leveler, putting tools of creation and dissemination in everyone’s hands and wresting control from long-established institutions and actors.” Taylor’s work seeks to show that the business imperatives underlying our technology has a dramatic effect on how we interact online and who, in the end, actually benefits from those interactions. I’m interested in this work to see how Free and Open Source software might resolve some of these concerns, or whether they will pose equally problematic issues.

Vaidhyanathan, Siva. The Googlization of Everything: (and Why We Should Worry). Berkeley: U of California, 2011. Print.

Vaidhyanathan’s work on Google is important to me, because, despite my critical concerns for Google, their series of produces — Gmails, Google search, and Google Drive — are hands down the most important tools that I use as a student, a worker and curious, interested citizen. In the development of Social Paper — which is messy, frustrating, and full of compromises — there have been times that I’ve wondered whether my critique of Google was rather alarmist, and that it was a waste of energy to try to create something that they will probably offer, and much more sophisticatedly, within a few years. Vaidhyanathan, and other writers discussed in this annotation, have been exceedingly helpful in these moments, by reaffirming the need to question the motives of the companies that are gaining an unprecedented amount of control in the most minute aspects of our professional and private lives.