Category Archives: Archives

Pforzheimer Collection at the NYPL

By: Sophia Natasha Sunseri

Like Chelsea, I visited the Shelley and his Circle Archives (part of the Pforzheimer Collection) at the NYPL. My experience also bore a resemblance to Chelsea’s in that I, too, encountered a somewhat agitated archivist who informed me that she wasn’t frustrated with me, but with the assignment (which, in her opinion, is too vague). Regardless, I proceeded with my research, albeit somewhat tentatively.

I was initially interested in perusing some of Mary Wollstonecraft’s manuscripts (and was specifically hoping to come across a working draft of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman [1792]). Some preliminary research revealed, however, that only two of Wollstonecraft’s working drafts are known to have survived: the first page of her essay “On Poetry” and a book review that she wrote. Thankfully, I was able to ascertain this information beforehand, as the NYPL’s online resources were quite useful. I refered to the library’s archives portal (https://wa.gc.cuny.edu/owa/?ae=Item&t=IPM.Note&id=RgAAAADEc%2fqmmQwMRauaFFPEeyqxBwCrCKyHOuKOTpLhQMMhSjpdBeuf4XH9AAACijVP6CjeSoftZudbrYoNAI1O47G7AAAJ) as well as to their published version of the Shelley and his Circle materials (Harvard UP, 1961-, 10 vols.), accessible here: http://catalog.nypl.org/record=b11093889~S1. Before my visit, I emailed the aforementioned archivist and requested to see correspondence between Mary Wollstonecraft and her sister, Everina Wollstonecraft, as well as the “On Poetry” manuscript.

In Mary Wollstonecraft’s letter to Everina (dated May 11-12, 1787), she discusses an ongoing monetary dispute with her brother, her experiences as a governess, a handful of French authors (especially Rousseau), and running into— and eventually snubbing—”Neptune,” an elegant but snobbish man for whom she once had affection. It is Wollstonecraft’s draft of “On Poetry,” however, that captivates my attention most. Although only one page of the draft survives (it is speculated to have originally been 11 quarto pages long) it affords much insight into Wollstonecraft’s revision process, which I find quite fascinating. Two published works are derived from this draft: an essay in the form of a letter to the editor of The Monthly Magazine, which was released in April of 1797 (http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008920340) and an essay published after Wollstonecraft’s death in September of 1797 under a new title assigned by Godwin: Posthumous Works of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman (with Godwin noting its origins in the preface). The differences between the two published versions are quite striking. The text from Posthumous Works most closely resembles the manuscript version (suggesting that it was most likely composed before The Monthly Magazine version). In this earlier version, Wollstonecraft employs simple vernacular: compare the phrase “the dream is over” (Posthumous Works) with the phrase “the reverie is over” (The Monthly Magazine). The text in the Monthly Magazine is ostensibly more baroque. Juxtaposing both works with what remains of the original manuscript reveals Wollstonecraft’s penchant to elaborate in her rewriting (it should be noted that Godwin did not heavily edit Wollstonecraft’s writing; he mostly made minor changes to punctuation). By assessing these primary source materials, I was able to draw conclusions that I otherwise wouldn’t have been able to.

While I did not find what I originally set out to find (a manuscript of one of Wollstonecraft’s better known works, like The Vindication of the Rights of Woman) it was interesting to observe that many of the ideas expressed in Wollstonecraft’s correspondences and in her essay draft were foregrounded in earlier works with which I am familiar (for example: her conflicted relationship to Rousseau; her rejection of highly stylized writing in favour of writing that communicates direct personal experience).

In the end, I was grateful that I came across materials that were previously unknown to me. It is this serendipitous aspect of archival research that I find most appealing—the accidental stumbling upon and the unexpected turns that one’s research may take as a direct result (which is one of the reasons why the archivist’s insistence upon a research project with such rigidly defined parameters irked me). I am looking forward to conducting more research at other archives in the city (and hopefully elsewhere).

Shelley and His Circle at the NYPL

By: Chelsea Wall

In the interest of full disclosure (and because I was probably the only one of us who had such an encounter), my experience with the New York Public Library archives began with a rather strange email exchange with one of the curators, whom I suppose should probably remain nameless. I filled out a request form to access the archives of Mary Wollestonecraft Shelley, to which this (slightly touchy) curator responded with a lecture on the vagueness of my assignment as well as a semantics lesson on the uses of “archive” vs. “archives.” This semantics lesson turned out to be incorrect, as I learned in a further email from said curator, however if anyone is interested in its nature, the singular form of “archives” is, in fact, “archives.”

Semantic quibbling aside, upon filling out the form, I received response rather quickly from multiple sources, though I was directed by the curator of the Berg Collection to consult the archives of Shelley and his circle, rather than the Mary Wollestonecraft Shelley archives, as vastly more of her papers are contained within the Pforzheimer Collection. The curator of that collection further requested that I consult the volumes of Shelley and His Circle before looking at the holdings of the archives, as many of the manuscripts are already published there, and I could potentially find them more useful than looking at the originals.

This brings me to draw upon a point that Sarah made in her posted assignment on her experience in the archives of the NYPL – it seems that access to manuscripts is quite guarded, and the filtration system to keep out the “riff raff,” so to speak, is rather extensive. While I fully understand the necessity of protecting two hundred year old documents, I remain discomfited by the privileging of access to and production of information and knowledge being restricted to those in higher-level education. The fact that I was asked to provide a reference in order to visit the archives speaks volumes to this point. As was pointed out in class, the creation of knowledge isn’t restricted to the institutions of academia, though we seem to have established a monopoly on primary sources and documents. I worry about what this privileging and micromanaging of access is doing to the production of knowledge through alternative avenues by denying access to primary documents to “amateur enthusiasts,” as if someone without a college education couldn’t use these sources in an appropriate manner.

Therefore, my search for information began in the second floor research area, where I, again like Sarah, was struck by the level of touristic noise and hullabaloo from the first floor below. Despite the nature of the library space as unconducive to quiet study and reflection, I did indeed find the volumes that I was instructed to look through quite informative. I focused on Mary Wollestonecraft Shelley’s correspondences rather than any manuscripts, in the interest of finding any reference to her neuroses regarding her failed pregnancies and determining their influence on the genesis of Frankenstein, which is rife with creation anxieties and motherless figures, intertwining life forces and death forces that are correspondent with Shelley’s lived experience. While I found nothing of this nature, after rifling through the 8 or so volumes of Shelley and His Circle, I decided to take a look at the letters written by Mary Wollestonecraft (Mary Shelley’s mother) to her childhood friend Jane Arden, written from 1773-1783. While they didn’t prove pertinent to any of my current work, I found it quite interesting to be privy to a private childhood squabble between Wollestonecraft and Arden, as if I was hearing a piece of juicy gossip some 225 years after the fact.

Though I didn’t find what I was looking for (though maybe I am an inadequate researcher), I was thankful to have some small experience with the daunting processes of archival research, and this assignment was effective in mediating my reluctance to engage with such processes. I refrained from taking pictures as I got the sense from our presentation on the archives at the NYPL some weeks ago that picture-taking is frowned upon, at least within this particular institution. However, I look forward to conducting research more pertinent to my work in other archives as well!

NYPL Archives: The Bryant-Godwin Papers

By: Sarah Hildebrand

I visited the New York Public Library’s archive of the Bryant-Godwin Papers. This collection is fairly expansive – 25 boxes worth of material including letters, diaries, manuscript drafts, notes, newspaper clippings, financial/legal records, and photographs. As many of you probably know, the NYPL has strict procedures for working with its materials, so I requested to look only at box 20, which contains William Cullen Bryant’s notebook and notes on agriculture and gardening. William Cullen Bryant was a 19th century poet and editor of the New York Evening Post; he also played a role in the creation of Central Park. I was interested to see how his observations of and interaction with the natural world may have informed his writing process and affected the production of meaning in his poetry, much of which would fall under the category of nature poems.

While in some aspects the NYPL has become a most horrid tourist trap (I’m always disappointed by its initial loudness and the presence of gift shops on the first floor), it also works surprisingly hard to keep the riff raff out of the archives. The building itself is a bit difficult to navigate if you’re actually looking for information rather than photo-ops. Few tourists would simply happen to stumble upon, let alone into, the Manuscripts and Archives Division, which is not only located at the end of an off-shooting hallway, away from the main corridor, but requires you to buzz in and wait to be escorted inside. This certainly says something about the privilege of, and access to, education/information. Something about checking all my items at the ground floor, minus a clear plastic bag and laptop, made me feel a bit like a felon, despite the conspicuous nature of my “breaking in” to the library.

Once arriving inside the Archives Division (and after signing-in several more times) I was presented with the box of items I had requested. I was instructed to only remove one folder from the box at a time and to keep everything in order (even though there didn’t appear to be much order to begin with). Inside the folders were William Cullen Bryant’s to-do lists of gardening chores – planting, transplanting, propagating. Various lists of plant species within his garden, as well as fastidious detailing of their locations. Several lists of “flowers in bloom” at Roslyn (his estate) on particular dates in October, sporadically throughout the years 1866-1877, as well as comments on that year’s weather. Next were various newspaper clippings on agriculture – mulching, pruning, cultivating, manuring, protecting against cuculio (a type of invasive insect), setting fence posts. It became clear that Bryant spent copious amounts of time both observing the outside world and actively laboring in it. Based on the plethora of newspaper clippings (an entire journal pasted with clippings, alongside a stack of free-floating articles), he was certainly interested in the natural world from a scientific perspective, as well as an aesthetic one.

While I didn’t stumble upon anything particularly relevant to my own projects, it was interesting to handle some 150-year-old documents and see what we have/haven’t learned about tree and plant care in that time. While some of the clippings were almost comically inaccurate (a combination of poor pruning cuts based on ill-researched newspaper articles probably led to the increased rate of tree disease and insect outbreaks he discovered at his estate) others were alarmingly informed. It is no wonder that Bryant constantly struggled to maintain his garden, and was careful to take his own copious notes about its progress. He was likely aware that a lot of his agricultural practices were somewhat experimental, and thus endeavored to document the outcomes and learn as much from his own experience as from what he read in the papers – knowledge that certainly came to inform his poetry.

The Lesbian Herstory Archives and the surprises of material culture

By: Iris Cushing

This past Monday morning I visited the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Park Slope, Brooklyn. I had been wanting to visit the LHA since encountering archive founder Joan Nestle’s writing on queer New York history last summer. The LHA is staffed entirely by volunteers; Kayleigh and Celeste were both there on Monday morning to show me around the space and tell me about how it works.

Founded in 1974 by writer Joan Nestle (whom Jennifer writes about in her previous post), the LHA existed for its first 15 years in Nestle’s Upper West Side apartment. With collectively-raised funds, the LHA was able to purchase a limestone building in Park Slope in 1990 to house its ever-growing holdings. The history of the space itself is fascinating. The ground floor features an extensive library of writing by and about lesbians, women, and a wide spectrum of queer discourses. The second floor contains extensive files about individual lesbians, as well as a materials related to lesbian history based on region and topic. In addition to material holdings, they also have digital audio, video and photo archives. The space is full of framed photos showing lesbian activists over the years, posters, and things like jean jackets bearing loads of buttons and patches–the physical correlates of a vibrant and diverse culture.

One goal I had in visiting the LHA was to see if they had any archival film footage (in any format) of poet Eileen Myles reading her poetry in the 70s, 80s or 90s. Recently I agreed to help a filmmaker named Catherine Pancake locate footage of Myles from this time period; I had found several films online, but wanted to see if there were any undigitized films (on VHS, for example) there at the LHA. Pancake is making a documentary about four New York-based lesbian artists and writers, including Myles and Jibz Cameron, whose recent work I’ve reviewed for Hyperallergic. Participating in Pancake’s material-gathering process for her documentary seems like a good opportunity to get some insight into one of my academic areas of interest: feminist and queer literary communities in postwar America in general, and in New York in particular.

I asked Kayleigh about the possibility of vintage Myles footage at the LHA; she looked Myles’ name up on the LHA’s database, but all that came up were Myles’ books and the biographical file on her. She told me I was welcome to look through the LHA’s VHS collection and see if I could find anything there, but warned me that there the VHS collection had not been organized in any way whatsoever, so it might take a long time. She led me to the kitchen, where the VHS tapes were arranged on a shelf in the corner. There were at least 500 of them, most of them home recordings with handwritten labels. They ranged from recordings of radical women’s collective meetings, to indy films, to DIY tapes of lesbian love scenes collaged together from mainstream movies. It seemed entirely likely that there could be Myles footage in there.

It was at this point that I looked around me and really considered the social and aesthetic nature of the LHA. The kitchen was occupied by a well-used copy machine that appeared to be at least 15 years old, a refrigerator decorated with hand-drawn fliers and rainbow magnets, and a coffee pot ringed with years’ worth of drip coffee. It reminded me, quite movingly, of many of the radical community activist spaces I spent time in on the West Coast: anarchist “infoshops” and feminist bookstores, places with necessarily nonhierarchical power structures and all-donated resources and time. The phenomenon of the LHA struck me as a subject of study unto itself (as, I suppose, all archives are). I felt drawn in by the physical qualities of the space, the smells and the light, the sense of how people have moved through the rooms over the years. It felt very alive and particular, an organic hybrid of library, museum, house, cafe, and something else that I can only describe as a sort of lesbian church.

I elected not to sort through the hundreds of VHS tapes, and headed upstairs to look at the biography files. Both the files and the library are organized by the subject or author’s first name, which I imagine is an anti-patriarchal organizing scheme, although I cannot find any mention of the alphabetizing scheme on the website. The file on Eileen was thick. I plunked down at the long oak table (half-covered with boxes of unsorted papers) and began to read.

The gathering of Myles-related letters, notes, fliers and clippings in the folder felt entirely appropriate both the LHA and to Eileen Myles herself–her poetry and her way of being in the world. Casual, funny, covertly challenging of “normal” social formalities. As I leafed through about a dozen mailed postcard notices for readings, addressed to Joan Nestle and bearing 19-cent stamps, an awesome sense of intimacy opened up. This felt like an archive that could only exist between friends, between living people who knew each other—one whose work is gathered, one who is doing the gathering—as opposed to a preservation of documents and artifacts from the past.

I was also fascinated by the sudden immediacy of the material nature of literary communities as they existed “back then” (in the 80s and 90s, in this case). A poet like Myles would have to send out Xeroxed postcards to people if she was having a reading, or releasing a new book; she would have to make posters to put up in bookstores. It struck me as odd that I had literally never considered the simple material and location-based ways in which literary events were promoted–and literary communities built– before the digital age. In that way, looking at these pieces of paper did feel like making contact with the past.

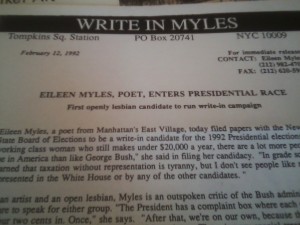

The majority of the Myles file was devoted to Myles’ 1992 write-in presidential campaign, which I had always known about (she includes it in her brief bio) but never knew the details of. In the chapter on Myles in Maggie Nelson’s Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions, Myles is quoted as saying that she talked about the campaign everywhere she went as it was happening, but she did not describe the writing and material-based elements of it. I was delighted to discover that the campaign, which Myles first announced in 1991, was a real grassroots campaign, complete with weekly Xerxoed letters to her constituency, posters, buttons, brochures, and information about rallies to support Myles’ candidacy. The letters include prose paragraphs and poems, and were wonderful to read: details about Myles’ childhood in Boston, her views on housing issues and homelessness, her claim that as a marginalized and poor person, she represents “the average American” more accurately than Bill Clinton or George Bush. It was wild to encounter a poet’s presidential campaign materials. To me, they are documents of a singularly unique literary project, almost a piece of performance art: joking but serious, propagandizing but also entirely liberating.

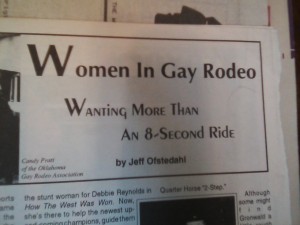

Before leaving, I decided to take a quick look at the “Regional” archives, a collection of sundry lesbiana organized by states within the US and by country. I took out the file for Arizona, where I used to live. The American Southwest, in my experience, is a site of both vehement homophobia AND radical queer countercultures (and everything in between); I was curious what kind of documentation of lesbian culture I would find in this file. There were things like brochures for women’s circles in Tucscon, newspapers about AIDS activism, posters for the first Gay Pride March in Phoenix. But what really blew my mind were the numerous newsletters and print ephemera about the lesbian rodeo scene in Arizona in the 80s and 90s. I had never imagined that lesbian rodeo riders existed, let alone a whole subculture devoted to promoting them and the culture (bars, dances, concerts, gatherings) surrounding them. Reading about these riders, their occupation of a historically very patriarchal space, resonated beautifully with the uncannily performative aspects of Myles’ presidential campaign. I ended up looking at that stuff until the LHA had to close for the day.

These encounters with the material traces of lesbian literary and social histories were tremendously eye-opening to me. I am looking forward to returning to the LHA, perhaps with the sole intention of sorting through those VHS tapes.