tactile poetry!

By: Erin Glass

For our archive assignment, I decided to go to the Poet’s House nestled inside the bottom two floors of a riverfront building in Battery Park. The website describes the Poet’s House as a national archive, but perhaps Wikipedia’s description of Poet’s House as a “literary center” is a bit more fitting, as the archives themselves seem to play only a small role in actual use of the space. Though their collection includes 60,000 books, chapbooks and literary journals, visitors typically come for one of their readings or other poetry-related events rather than to peruse their shelves. Or at least so it seems. Personally, my first few visits to the Poet’s House were entirely event related. And now that I finally had a chance to check out their holdings — along with co-explorer Seth — I had the distinct sense we were treading a sort of forgotten frontier. The window side tables were full of laptopped students, perhaps some even enjoyed poetry in addition to sunlit work spaces, but once near the actual heart of the archive, the population dropped.

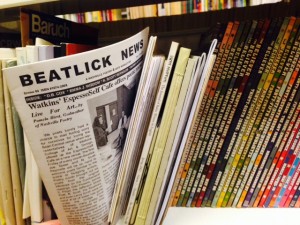

the wall of new poetry.

Such is often the case with libraries, archives, so no criticism here. The sunlit windows, the free wifi, the poetry readings and classes, are all equally important organs for the vitality of such a literary center. It was one of the events, in fact, that made me so eager to explore their actual collection. No other institution in my experience, save perhaps for the university itself, has so successfully drawn my interest and activity to its bibliographic holdings through events.

Let me explain. A year or two ago, I attended a talk about the history of the chapbook at the Poet’s House that was held in conjunction with The Center for the Humanities annual Chapbook Festival. Now just in case anyone here isn’t exactly sure what a chapbook is, let us briefly recollect. Wikipedia nicely describes the chapbook’s contemporary form as:

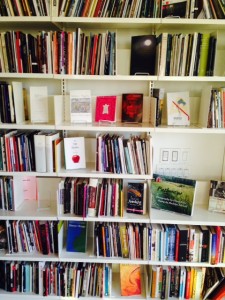

chapbook shelves

…publications of up to about 40 pages, usually poetry bound with some form of saddle stitch, though many are perfect bound, folded, or wrapped. These publications range from low-cost productions to finely produced, hand-made editions that may sell to collectors for hundreds of dollars…The genre has been revitalized in the past 40 years by the widespread availability of first mimeograph technology, then low-cost copy centers and digital printing, and by the cultural revolutions spurred by both zines and poetry slams, the latter generating hundreds upon hundreds of self-published chapbooks that are used to fund tours.

The chapbook is the folk press, a means of distributing one’s texts outside the pearly gates of conventional publishing. It is perhaps the most important — and unruly! — form of underground poetry movements in 20th century United States. One need not have the approval of an editor or the capital of a printing press, but only the gumption to turn available resources into the means of transmission. And so a survey of chapbooks of the past sixty years brings forth all sorts of shapes, materials and styles that defy traditional expectations of a published book. Without a standardized means of production, the chapbook’s form depended largely on its creator’s imagination.

But back to the talk. The speakers articulated some of the historical roots of the chapbooks in early modern Europe, and then described some of the genre’s major transformations in the past century. For example, tools and organizations that in many ways made chapbook publishing a far more accessible, sustainable, and influential endeavor also contributed to the homogenization of the form. Prior to the Xerox machine, chapbook makers essentially had to individually determine the materials, forms and style of the chapbook, which enforced, so to speak,diversity within the genre. Additionally, one speaker linked the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts in 1965 — which did important work cultivating some of these chapbook endeavors into shinier, more professional, more public forms — with the waning of a DIY, rough-edged culture of chapbook makers. While no one was arguing that the Xerox machine or the NEA were not much welcome resources for fringe cultural producers, the speakers quite effectively demonstrated how diversity, reach, and sustainability of cultural production are all dramatically influenced by available resources, and not always in the way we expect. When the talk ended we were left to explore a curated selection of chapbooks from the fifties and sixties that highlighted the dramatic range of creativity in publishers that worked with minimal resources and support. Somehow, I walked away that night thinking that the curated display just represented the tip of the iceberg. I was flooded with visions of combing through the past century of our nation’s folk publications. How on earth, I wondered, would they even catalog such an oddball, odd-shaped, uncategorizable set of items. Oh, I’d return, all right.

But when I did return — a few Fridays ago — making my way past the first shelf of this year’s published books of poetry, past the shelves devoted to international poetry, past the books of criticism, journals, memoirs, dictionaries, past, really, the entire printed discourse related to English poetry, all the way to the very back to its chapbook collection, I realized my imagination had perhaps run away from me. Here, in about two aisles, lies the Poet’s House chapbook collection. Unruly, surprising, impressive, yes — one might find hand decorated, stapled, glitter explosive works snugly sharing shelf space with more official works by the likes of Louise Gluck — but hardly the National Library of Chapbooks that I had somehow been expecting. I browsed through the mildly alphabetized materials, losing interest as it seemed most were produced in the last ten years, and all off an Epson printer. Where, then, I wondered, did the nation’s history of chapbooks exist?