from http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/41xnXzmzpGL._SY344_BO1,204,203,200_.jpg

This discussion of Professing Literature: An Institutional History by Gerald Graff[1] is based on the idea that, as stated by David Gillborn, “the most dangerous form of ‘white supremacy’ is not the obvious and extreme fascistic posturing of small neo-nazi groups, but rather the taken-for-granted routine privileging of white interests that goes unremarked in the political mainstream” (485).[2] This subtle, heightened form of white supremacy can be found easily throughout the history (and contemporary) teaching of English in the United States, yet – disturbingly – in his history of English studies in the U.S. academy, Graff elides and sometimes even excuses this racism.

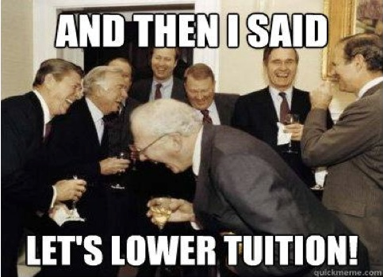

Graff paints an idealized history in which the field-coverage principle[3] allows for the accommodation of “disruptive” areas such as “contemporary literature, black studies, feminism, Marxism, and deconstruction” without “paralyzing” the whole of the department (7). (Ableist use of dis/ability as a metaphor aside, shouldn’t the goal of these areas and methods of study be precisely to disturb the entire department structurally, rather than to merely be ‘tacked on’ to avoid challenging anyone’s privilege?) He writes that newer (and presumably, according to his analysis, less racist) critics in English will encounter protests from “senior” (and presumably, according to his analysis, more racist) faculty members, but when these people (men) retire, “his replacement [will] most likely [be] somebody who had quietly assimilated the [new] critical methods, with the offensive prejudices smoothed away” (194).

The narrative this creates is one of relentless positivism: it creates a story in which the history of English teaching is shaped by a linear progression of always getting better, always getting less racist, misogynist, etc., simply by the progression of time and the waiting for racist, misogynist, etc., faculty to retire. This is enormously problematic, as is any argument that constructs history as a progressive “it gets better” (Dan Savage? Ick!) narrative.

(“‘The civil rights movement happened, Obama got elected, hooray, let’s all be ‘colorblind’ and postracial!’

‘NO. BECAUSE MASS INCARCERATION THOUGH.’”)

Equally alarmingly, Graff dismisses concerns about the whiteness and maleness and straightness and ableist-ness and middle classness and need-I-go-on-ness of the literary canon. He comforts readers by claiming that, “it was up to each instructor (within increasingly flexible limits) to determine method and ideology without correlation to one another” (9). In other words, a hegemonic canon is fine, because you never know who’s teaching it: you might have an anti-racist professor in there somewhere, and that makes it all better.

from http://www.memecreator.org/static/images/memes/248743.jpg

Oddly enough, Graff acknowledges later that there is a question of “whether the effectiveness of teaching can be fairly measured apart from the institutional forms that shape it” (227). Surely not. Surely an evaluation of all teaching is subject to an evaluation of the institutions in which this teaching occurs. And if this is the case, it is a problem greater than relying on individual teachers to subvert it that the canon is what the canon is, with the occasional obligatory Baldwin and the rarer, partially obligatory Walker tacked on.

Tacking on has been a revolutionary, radical starting point – for example, adding women’s studies programs into English programs, as Graff mentioned above – but that is what it has been: a starting point. We cannot write off the vast history of oppression within English education (and education more broadly) – Who are most of our professors? What texts do we make our students read? What dialect of English do we make them write in? Who has and has had unfettered access to “higher” education, anyway? – by taking permanent solace in a starting point.

from http://carmenkynard.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Screen-shot-2012-02-15-at-1.04.04-PM.png

So what do I propose? That any history of English education in the U.S. examine that history through postcolonial, queer feminist, and critical disability lenses. The results will be more complicated than narrating the debates between white men over the years (which is most of Graff’s book), but such a reading would also be infinitely more rewarding.

————————————————————————————–

[1] Graff, Gerald. Professing Literature: An Institutional History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

[2] Gillborn, David. “Education Policy as an Act of White Supremacy: Whiteness, Critical Race Theory and Education Reform.” Journal of Education Policy 20.4 (2005): 485-505.

[3] This principle states that the prominence of different fields within English departments encourage an expanded breadth of coverage of topics while discouraging interaction between interrelated but discretely listed fields (6-7).