By: Catherina Sara Engh

Two Fridays ago, I visited the Morgan reading room where I looked at two oversized books of satirical prints drawn by the English caricature artist James Gillray. The experience was excellent, the librarians were helpful and getting into the reading room was as easy as could be expected. I was asked to stow my things—everything but a laptop, my iphone and a few papers–in a locker. I washed my hands and gave my driver’s license to a librarian to photocopy. Inside the reading room, someone had already pulled the two books that I requested and a librarian set one of them up for me on a stand.

The first book that I looked through was approximately two by four feet–very cumbersome—and consisted of 307 pages with Gillray prints pasted into the books’ pages. I stood to look at the prints and used a weight to hold the pages in place. The second book was much lighter, with fewer pages.

In her book The Golden Age of Caricature, Diana Donald argues that caricatures don’t fit neatly into the categories of high or low art. In the drawings, allegorical content is mixed with impolite subject matter. At the Morgan, for instance, I saw a print of the Queen of England on a Toilet titled ‘Patience on a Monument’—a line from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. The mixture of high and low formal qualities and the cross-class audience—in the 1790s and today—makes the status of caricatures on the art market complex. Seeing so many prints pasted into the pages of this book, I couldn’t help but think that whoever put the collection together did not consider these etchings very valuable. (The collection I saw was given to the Morgan by Gordon N. Ray, who acquired them in 1815, but it’s unclear who owned them before him.)

The visit was, as I had hoped, productive to my research and thinking. I’m working on a paper that focuses on representations of English women in the 1790s world of fashion. Before the visit, I made a list of all the caricatures that I hoped to see and I left having seen seven of ten. It was great to get photos of details that I won’t find in a Google image search.

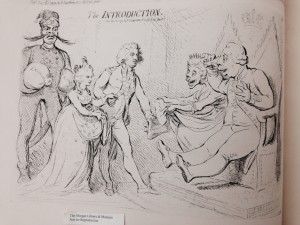

As I looked for the prints that I knew I wanted to see, I came across several that will help me prove my argument. This print –‘The Introduction’–pictures Frederick, the Prince regent, (in 1791) presenting his wife Charlotte to King George III and Queen Sophia. Charlotte’s apron is overflowing with gold coins. Behind her is an unfortunate depiction of an orientalized Prussian man who stands guarding more of her money. I’ll have to see if I can find a good account of Charlotte and the dowry she brought into her marriage with the Prince. The laugh here is at the expense of the crown. The Prince was notoriously in debt to the crown and this marriage must have been a mercenary one. In my paper, I want to talk about how Gillray links marriage to the market and social spectacle to financial speculation. So, for my purposes, the print is great—it depicts marriage as a transaction. The King and Queen value Charlotte for the money that she brings to the marriage, regardless of where it came from.

The other great find was a series called ‘Progress of the Toilet’ which includes ‘The Stays’ ‘The Wig’ and ‘Dress Completed.’ In these drawings, a woman stands dressing before a mirror—a common enough setting for a Gillray print. But on the wall is a framed image depicting the time of day—morning, noon and evening in respective prints. Gillray exaggerates to comic proportions the time it takes this woman to get dressed, even with the help of a servant. In Catharine, or the Bower, Jane Austen uses a similar comic technique—she exaggerates a rakish character’s dressing time to indicate his foppishness and to suggest to her reader that he’s not morally serious.

It was great to see the prints as they were originally sized. I noticed details like the pictures of morning, noon and night in the ‘Progress of the Toilet’ series that I probably wouldn’t otherwise have noticed. The size of the prints made the intricacies of Gillray’s line and shading techniques more apparent and impressive. When people write about caricature prints, they usually discuss ‘supercharged features’ and, indeed, I noticed that the monstrous proportions of facial features instantly indicate who to laugh at or, more strongly, disdain. The queen, wherever she is pictured (see ‘The Introduction’), appears monstrous. I also noticed a lot of tavern drawings and admired up close the compositional arrangement of these overcrowded, busy scenes .

Finally, I saw a number of dreamscapes—drawings of Tom Paine or the Prince Regent asleep in a bed, surrounded by dream imagery. In his essay ‘The Cartoonist’s Arsenal,’ E.H. Gombrich applies Freud’s theories of compression and displacement to his readings of caricature prints. Before this trip, I was a little skeptical of Gombrich’s Freudian approach. But seeing the many dream scenes included in the book of collected prints, I was convinced that the Freudian approach is a good one and that Gillray’s kind of comedy expresses a thorough knowledge of human psychology.