The past couple of weeks, I have found myself intimately invested in our conversations in class. I tried to articulate some of the things that were going on for me – apparently with some success (thanks for the shout-out, Lindsey! Right back at you!) – but I’m going to use this as a space to work through some more thoughts. I’m going to do this by attempting to interweave our discussions of Planned Obsolescence and the Agrippa files.

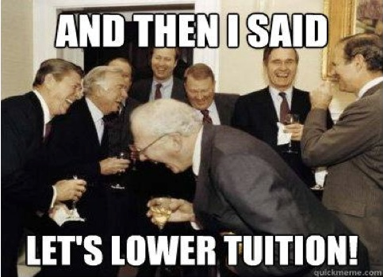

Something that has persistently stuck with me about our conversation two classes ago (Planned Obsolescence and open access) was the ways that so many of us insisted that open access is a proverbial enemy of the academy. We risk diluting the power and importance of our work, I kept hearing, if we open up access to academic literature. I agree: open access does threaten current power and notions of importance. It’s just… I like that. I don’t feel threatened by that. I feel invigorated by that. I think the educational privileges we all have in our class should be not only opened up, but dismantled. Which people and systems benefit from reinforcing an elite set of knowledges and an elite set of privileges attendant with guarding academic knowledge from “the public” (what does that even mean?)? I would argue that the answer to that is a very race- and class-based one in which racial and class injustices are perpetuated by limited or closed access to academic spaces.

Open access helps academic knowledge and discourse not slip into the realm of the obsolete. And it is obsolete if we are insisting on our research remain solely in the purview of other educationally privileged academics. And, without open access, the obsolescence of academia is planned (look! A connection between our readings!), is deliberate, is designed. Academic work can be solid from the academy’s perspective, but obsolete in the fact of it slipping out of relevance if it doesn’t somehow have material effects on people’s lives. And open access not only permits these material effects by allowing people who don’t necessarily have the educational or economic privileges needed to access materials to encounter potentially transformative academic content, but – perhaps most importantly – allows the lived experiences of people’s lives to impact the actual content of academic work. Isn’t that awesome? If we don’t advocate for that, aren’t we privileging only certain kinds of elite knowledges as valid knowledges? Let’s check out the academy in general, and the structures of racist and classist oppression that shape it and who can participate in it. Whose knowledges does that mean we’re privileging? (Hint.) My point is, open access can be a crucial tool for promoting racial and economic justice, in the same way that closed/limited access perpetuates these injustices through legitimating only certain kinds of knowledges and languages.

This seems to me to be intimately connected to the ways that we discussed the Agrippa files. As Lindsey so deliciously articulated (I kind of just want to re-post her whole thing), Agrippa represented a mode of resistance to the expected norms of textual re-presentation and interpretation. We privilege what we can take our time with, what we can read back and watch back and analyze again and again. Temporally, this seems to me to de-privilege moment-by-moment experiences and living – moments that cannot be recorded, cannot be captured, cannot be made intelligible to an audience – as less important than what can be made recordable and therefore visible and (possibly) intelligible to someone else (someone academic) for analysis. Here, there is so much potential for art and performativity to intervene, and I love that… The flash of individual experience; the invisible, momentary interactions with non-textual encounters; the internalized trauma of microaggression after microaggression that cannot be recorded because these violences defy such simple identification; the e/affects aroused by snippets of songs, flashes of color, and secret eye sex with a maybe-more-than-friend; these are what we miss out on when we privilege what can be recorded, what can be archived, what can be examined over and over again.

Thoughts?