By: Iris Cushing

This past Monday morning I visited the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Park Slope, Brooklyn. I had been wanting to visit the LHA since encountering archive founder Joan Nestle’s writing on queer New York history last summer. The LHA is staffed entirely by volunteers; Kayleigh and Celeste were both there on Monday morning to show me around the space and tell me about how it works.

Founded in 1974 by writer Joan Nestle (whom Jennifer writes about in her previous post), the LHA existed for its first 15 years in Nestle’s Upper West Side apartment. With collectively-raised funds, the LHA was able to purchase a limestone building in Park Slope in 1990 to house its ever-growing holdings. The history of the space itself is fascinating. The ground floor features an extensive library of writing by and about lesbians, women, and a wide spectrum of queer discourses. The second floor contains extensive files about individual lesbians, as well as a materials related to lesbian history based on region and topic. In addition to material holdings, they also have digital audio, video and photo archives. The space is full of framed photos showing lesbian activists over the years, posters, and things like jean jackets bearing loads of buttons and patches–the physical correlates of a vibrant and diverse culture.

One goal I had in visiting the LHA was to see if they had any archival film footage (in any format) of poet Eileen Myles reading her poetry in the 70s, 80s or 90s. Recently I agreed to help a filmmaker named Catherine Pancake locate footage of Myles from this time period; I had found several films online, but wanted to see if there were any undigitized films (on VHS, for example) there at the LHA. Pancake is making a documentary about four New York-based lesbian artists and writers, including Myles and Jibz Cameron, whose recent work I’ve reviewed for Hyperallergic. Participating in Pancake’s material-gathering process for her documentary seems like a good opportunity to get some insight into one of my academic areas of interest: feminist and queer literary communities in postwar America in general, and in New York in particular.

I asked Kayleigh about the possibility of vintage Myles footage at the LHA; she looked Myles’ name up on the LHA’s database, but all that came up were Myles’ books and the biographical file on her. She told me I was welcome to look through the LHA’s VHS collection and see if I could find anything there, but warned me that there the VHS collection had not been organized in any way whatsoever, so it might take a long time. She led me to the kitchen, where the VHS tapes were arranged on a shelf in the corner. There were at least 500 of them, most of them home recordings with handwritten labels. They ranged from recordings of radical women’s collective meetings, to indy films, to DIY tapes of lesbian love scenes collaged together from mainstream movies. It seemed entirely likely that there could be Myles footage in there.

It was at this point that I looked around me and really considered the social and aesthetic nature of the LHA. The kitchen was occupied by a well-used copy machine that appeared to be at least 15 years old, a refrigerator decorated with hand-drawn fliers and rainbow magnets, and a coffee pot ringed with years’ worth of drip coffee. It reminded me, quite movingly, of many of the radical community activist spaces I spent time in on the West Coast: anarchist “infoshops” and feminist bookstores, places with necessarily nonhierarchical power structures and all-donated resources and time. The phenomenon of the LHA struck me as a subject of study unto itself (as, I suppose, all archives are). I felt drawn in by the physical qualities of the space, the smells and the light, the sense of how people have moved through the rooms over the years. It felt very alive and particular, an organic hybrid of library, museum, house, cafe, and something else that I can only describe as a sort of lesbian church.

I elected not to sort through the hundreds of VHS tapes, and headed upstairs to look at the biography files. Both the files and the library are organized by the subject or author’s first name, which I imagine is an anti-patriarchal organizing scheme, although I cannot find any mention of the alphabetizing scheme on the website. The file on Eileen was thick. I plunked down at the long oak table (half-covered with boxes of unsorted papers) and began to read.

The gathering of Myles-related letters, notes, fliers and clippings in the folder felt entirely appropriate both the LHA and to Eileen Myles herself–her poetry and her way of being in the world. Casual, funny, covertly challenging of “normal” social formalities. As I leafed through about a dozen mailed postcard notices for readings, addressed to Joan Nestle and bearing 19-cent stamps, an awesome sense of intimacy opened up. This felt like an archive that could only exist between friends, between living people who knew each other—one whose work is gathered, one who is doing the gathering—as opposed to a preservation of documents and artifacts from the past.

I was also fascinated by the sudden immediacy of the material nature of literary communities as they existed “back then” (in the 80s and 90s, in this case). A poet like Myles would have to send out Xeroxed postcards to people if she was having a reading, or releasing a new book; she would have to make posters to put up in bookstores. It struck me as odd that I had literally never considered the simple material and location-based ways in which literary events were promoted–and literary communities built– before the digital age. In that way, looking at these pieces of paper did feel like making contact with the past.

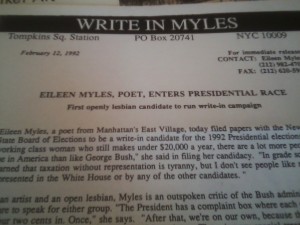

The majority of the Myles file was devoted to Myles’ 1992 write-in presidential campaign, which I had always known about (she includes it in her brief bio) but never knew the details of. In the chapter on Myles in Maggie Nelson’s Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions, Myles is quoted as saying that she talked about the campaign everywhere she went as it was happening, but she did not describe the writing and material-based elements of it. I was delighted to discover that the campaign, which Myles first announced in 1991, was a real grassroots campaign, complete with weekly Xerxoed letters to her constituency, posters, buttons, brochures, and information about rallies to support Myles’ candidacy. The letters include prose paragraphs and poems, and were wonderful to read: details about Myles’ childhood in Boston, her views on housing issues and homelessness, her claim that as a marginalized and poor person, she represents “the average American” more accurately than Bill Clinton or George Bush. It was wild to encounter a poet’s presidential campaign materials. To me, they are documents of a singularly unique literary project, almost a piece of performance art: joking but serious, propagandizing but also entirely liberating.

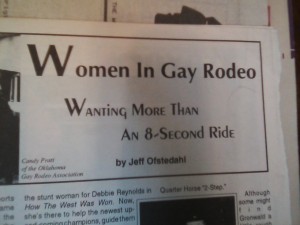

Before leaving, I decided to take a quick look at the “Regional” archives, a collection of sundry lesbiana organized by states within the US and by country. I took out the file for Arizona, where I used to live. The American Southwest, in my experience, is a site of both vehement homophobia AND radical queer countercultures (and everything in between); I was curious what kind of documentation of lesbian culture I would find in this file. There were things like brochures for women’s circles in Tucscon, newspapers about AIDS activism, posters for the first Gay Pride March in Phoenix. But what really blew my mind were the numerous newsletters and print ephemera about the lesbian rodeo scene in Arizona in the 80s and 90s. I had never imagined that lesbian rodeo riders existed, let alone a whole subculture devoted to promoting them and the culture (bars, dances, concerts, gatherings) surrounding them. Reading about these riders, their occupation of a historically very patriarchal space, resonated beautifully with the uncannily performative aspects of Myles’ presidential campaign. I ended up looking at that stuff until the LHA had to close for the day.

These encounters with the material traces of lesbian literary and social histories were tremendously eye-opening to me. I am looking forward to returning to the LHA, perhaps with the sole intention of sorting through those VHS tapes.