Author Archives: Jenn Polish

Synthesizing Too Many Thoughts – Agrippa, Obsolescence, and Academic Elitism

The past couple of weeks, I have found myself intimately invested in our conversations in class. I tried to articulate some of the things that were going on for me – apparently with some success (thanks for the shout-out, Lindsey! Right back at you!) – but I’m going to use this as a space to work through some more thoughts. I’m going to do this by attempting to interweave our discussions of Planned Obsolescence and the Agrippa files.

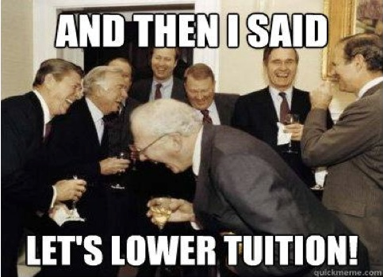

Something that has persistently stuck with me about our conversation two classes ago (Planned Obsolescence and open access) was the ways that so many of us insisted that open access is a proverbial enemy of the academy. We risk diluting the power and importance of our work, I kept hearing, if we open up access to academic literature. I agree: open access does threaten current power and notions of importance. It’s just… I like that. I don’t feel threatened by that. I feel invigorated by that. I think the educational privileges we all have in our class should be not only opened up, but dismantled. Which people and systems benefit from reinforcing an elite set of knowledges and an elite set of privileges attendant with guarding academic knowledge from “the public” (what does that even mean?)? I would argue that the answer to that is a very race- and class-based one in which racial and class injustices are perpetuated by limited or closed access to academic spaces.

Open access helps academic knowledge and discourse not slip into the realm of the obsolete. And it is obsolete if we are insisting on our research remain solely in the purview of other educationally privileged academics. And, without open access, the obsolescence of academia is planned (look! A connection between our readings!), is deliberate, is designed. Academic work can be solid from the academy’s perspective, but obsolete in the fact of it slipping out of relevance if it doesn’t somehow have material effects on people’s lives. And open access not only permits these material effects by allowing people who don’t necessarily have the educational or economic privileges needed to access materials to encounter potentially transformative academic content, but – perhaps most importantly – allows the lived experiences of people’s lives to impact the actual content of academic work. Isn’t that awesome? If we don’t advocate for that, aren’t we privileging only certain kinds of elite knowledges as valid knowledges? Let’s check out the academy in general, and the structures of racist and classist oppression that shape it and who can participate in it. Whose knowledges does that mean we’re privileging? (Hint.) My point is, open access can be a crucial tool for promoting racial and economic justice, in the same way that closed/limited access perpetuates these injustices through legitimating only certain kinds of knowledges and languages.

This seems to me to be intimately connected to the ways that we discussed the Agrippa files. As Lindsey so deliciously articulated (I kind of just want to re-post her whole thing), Agrippa represented a mode of resistance to the expected norms of textual re-presentation and interpretation. We privilege what we can take our time with, what we can read back and watch back and analyze again and again. Temporally, this seems to me to de-privilege moment-by-moment experiences and living – moments that cannot be recorded, cannot be captured, cannot be made intelligible to an audience – as less important than what can be made recordable and therefore visible and (possibly) intelligible to someone else (someone academic) for analysis. Here, there is so much potential for art and performativity to intervene, and I love that… The flash of individual experience; the invisible, momentary interactions with non-textual encounters; the internalized trauma of microaggression after microaggression that cannot be recorded because these violences defy such simple identification; the e/affects aroused by snippets of songs, flashes of color, and secret eye sex with a maybe-more-than-friend; these are what we miss out on when we privilege what can be recorded, what can be archived, what can be examined over and over again.

Thoughts?

Annotated Bibliography – Maleficent!

By: Jennifer Polish

I’m working on a book chapter on the intersections between animality and dis/ability in the movie Maleficent (super exciting, right?!), so this annotated bibliography emerges mostly from the beginnings of that research. As you might notice (or have picked up on in class!), I’m interested in privileging “non-scholarly” texts, and my interest in the theoretical productions of Temple Grandin’s memoir(s) here is something that I hope can approach that de-privileging of “scholarly texts” and the elevation of “non-scholarly” works and knowledge formations. Onward!

Diaval and Maleficent

Clark, Emily. Voiceless Bodies: Feminism, Disability, Posthumanism. Diss. University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2012.

This dissertation mostly focuses on the intersections between women’s bodies and dis/abled bodies. Clark’s chapter focusing on J.M. Coetzee’s female characters who “speak for those who cannot speak for themselves” (in respective cases, a dis/abled human and factory farmed non/humans) argues that Coetzee’s texts promote “voicelessness” as a “force” rather than a passive object, something which ‘voiceness’ cannot hope to accurately represent. This argument is salient and has been used to great effect by people like Temple Grandin, who assert silence and multiple forms of communication as equally valid. The connections here between animality and disability is clear, and this is one of the crucial points I am interested in drawing forth in my own work.

Grandin, Temple. Thinking in Pictures. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009.

Refiguring her “disability” as an enabling force of understanding between non/humans and humans rather than a disabling obstacle, Grandin deconstructs the binaries of human and nonhuman, ability and disability. Her methodology breaks down these binaries in a way that makes the intersections between species-based and ability-based oppression extremely clear. The use of memoir as the form through which to make these powerful material and theoretical interventions reinforces Grandin’s points about the damage done by privileging only certain, recognized forms of communication. By presenting such valuable theoretical arguments in the form of a memoir, Grandin performs exactly that which she is calling her audience’s attention to.

Laforteza, Elaine M. “Cute-ifying Disability: Lil Bub, the Celebrity Cat.”M/C Journal 17.2 (2014).

This article analyzes the rise of “cute animals” in online spaces. Paying particular attention to “cute disabled animals”, Laforteza explores the underlying lack of regard for dis/abled and non/human subjectivity and agency implicit in the popularization of these objectifying and commodifying images. This can be useful for my own work in that it explicitly critiques the “positive” objectification of both dis/ability and animality – while at the surface, the “cute animal” phenomenon seems like it is positively representing animals, it does tremendous harm (much like Robert McRuer’s analysis of dis/ability in As Good as it Gets).

Mills, Brett. “Invalid Animals: Finding the Non-Human Funny in Special Needs Pets.” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 7.3 (2013): 321+.

In his analysis of advertisements for a UK-based documentary “Special Needs Pets,” Mills discusses the interconnections between the treatment of humans with disabilities and animals vis a vis the documentary’s portrayal of non/humans with dis/abilities. While he examines the potential of the documentary to (inadvertently, it seems) unsettle definitions of disability, he also critiques the documentary as a call to objectify people with dis/abilities as comic relief. This “comic relief” was provided by the raven character Diaval in the summer film Maleficent, so this article might prove very useful in my and Carrie’s analysis of dis/ability and animality in that film.

Nussbaum, Martha. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007.

In taking a distinctly liberal approach (as opposed to the more radical approaches of much of critical disability studies) to disability studies, Nussbaum offers a call for equity based not on a social contract (which cannot be valid between people[s] without equal power), but on someone’s “capabilities,” Nussbaum unites discussions of animal studies and of disability studies in one text. While doing so, she advances a claim for cross-species equity as an issue of social justice. Though her insistence on liberalism hinders the usefulness of her analysis, her specific attention to “capabilities” has the potential to work in a radical space of redefining power relationships by access-based, socially-formulated material realities.

Rubio, Fernando Domínguez. “HaciaunaTeoría Social Post-Humanista: El Caso del Síndromede Cautiverio.” Política y Sociedad 45.3 (2009): 61-73.

This article argues that any posthumanist study of non/humans and humans should not set itself up at the binaristic opposite of humanist studies. Rather, posthumanism should be understood as a new way to pose questions about what it means to be human, opening analyses up for more generative questions about the value of divisions between human and other-than-human beings, rather than getting preoccupied with questions of whether “the human” no longer exists (if it ever did). Calling out this preoccupation is essential in a field that often does get too caught up in the definitional boundaries of “humanity” rather than pushing the concept to its absolute limits to generate new kinds of knowledge and materialities.

Salomon, Daniel. “From Marginal Cases to Linked Oppressions: Reframing the Conflict Between the Autistic Pride and Animal Rights Movements.” Journal for Critical Animal Studies 8.2 (2010): 47-72.

This article takes as its starting point conflicts between autistic pride and animal rights discourses, using Peter Singer’s “Argument from Marginal Cases” as a point of departure. Salomon ultimately argues that increasing our understanding of the “linked oppressions” of humans and nonhumans will enable a diffusion of tensions and a fruitful means of moving forward. Taking two fronts that are generally considered marginal – dis/ability activism and animal activism – and uniting them, not by nature of their marginality, but by nature of the intimate linkages between the forms of oppression that define them, Salomon performs an important theoretical intervention into activist scholarship, which I hope to continue in my work.

Subercaseaux, Bernardo. “Perros y Literatura: Condición Humana y Condición Animal.”Atenea (Concepción) 509 (2014): 33-62.

An analysis of representations of dog-human relationships in modern literary imaginings, this article explores the mascot-ification of the dog figure that accompanied the late capitalistic fetishization of animal representations of human aspirations and desires. The correlation between humans and dogs produced in the real world is reflected in and perpetuated by literature, which often portrays dogs as more successfully performing humanity than humans. This work can be particularly helpful when analyzing (which I am not doing, but I know other people are interested in this) Victorian literature that deals with “domestic animals.”

Weil, Kari. “Killing Them Softly: Animal Death, Linguistic Disability, and the Struggle for Ethics.” Configurations: A Journal of Literature, Science, and Technology 14.1-2 (2006): 87-96.

Using the work of author Temple Grandin to help her formulate her arguments, Weil asserts that Grandin’s notion of human vision screening profoundly connects literary, disability, and animal studies. Framing human language as an obstacle rather than a portal to knowledge, Weil unsettles the ableist and speciesist notion that non-lingual communication is indicative of ‘lower-level’ communication. Intervening at the level of the literary, Weil makes the important move of bringing the animal-dis/ability discourse into the discourse of the ethics of language usage in writing, speaking, and classroom teaching.

Wolfe, Cary. “Learning from Temple Grandin, or, Animal Studies, Disability Studies, and Who Comes After the Subject.” Mars 27 (1994): 12.

Also utilizing the work of Temple Grandin as his premise, Wolfe argues that the sub-genre of people with dis/abilities who write about the dis/ability as an ability to enhance communication with non/humans has extremely generative power at the intersection of disability and animal studies. These works push scholarship forward beyond liberal humanism. Additionally, these works give true meaning to the linguistic formation of dis/ability and non/human (as opposed to disability and nonhuman), because they offer material (rather than strictly theoretical) objections to the portrayal of dis/ability as solely disabling (hence the insertion of the slash, which problematizes that assumption).

State of the (Children’s/YA Lit) Field

By: Jennifer Polish

Journals

The Lion and the Unicorn: “The Lion and the Unicorn is a theme- and genre-centered journal of international scope committed to a serious, ongoing discussion of literature for children.”

Bookbird: “Published by the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), Bookbird communicates new ideas to the whole community of readers interested in children’s books, publishing work on any topic in the field of international children’s literature.”

Children’s Literature: “Children’s Literature is the annual publication of the Modern Language Association Division on Children’s Literature and the Children’s Literature Association. Encouraging serious scholarship and research, Children’s Literature publishes theoretically based articles that address key issues in the field.”

Children’s Literature Association Quarterly: “With a new look and a new editorial staff, the Children’s Literature Association Quarterly continues its tradition of publishing first-rate scholarship in Children’s Literature Studies.”

Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures: “Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures is an interdisciplinary, refereed academic journal whose mandate is to publish research on, and to provide a forum for discussion about, cultural productions for, by, and about young people.”

Books Published in the Last Two Years

Hintz, Carrie, Balaka Basu, and Katherine R. Broad, eds. Contemporary Dystopian Fiction for Young Adults: Brave New Teenagers. Routledge, 2013.

McGillis, Roderick. Voices of the Other: Children’s Literature and the Postcolonial Context. Routledge, 2013.

Zipes, Jack. Sticks and Stones: The Troublesome Success of Children’s Literature from Slovenly Peter to Harry Potter. Routledge, 2013.

Annual Conferences (Recent/Upcoming)

National Latino Children’s Literature Conference:

“Connecting Cultures and Celebrating Cuentos”

March 13-14, 2014

The University of Alabama

Children’s Literature Association Conference:

“Give me liberty, or give me death!”:

The High Stakes and Dark Sides of Children’s Literature

Hosted by Longwood University

June 18-20, 2015

Richmond, Virginia

Omni Richmond Hotel

Western Washington University Children’s Literature Conference:

2015 WWU Children’s Literature Conference

Saturday, February 28, 2015

Performing Arts Center ~ Concert Hall

Stony Brook Southampton Children’s Literature Conference:

Workshops in Writing Picture Books, Middle Grade Fiction and Young Adult Novels

July 16-20, 2014

University Press Series

Oxford University Press School and Young Adult Books: (Not an academic series per se, but if not more important) “Oxford University Press is the only university press that publishes books for children and young adults, an effort that is a direct extension of the Press’s mission to disseminate knowledge to a broad public.”

University Press of Mississippi Children’s Literature Association Series: “Books in this series include critical assessments of books, authors, illustrators, presses, and other entities involved in children’s and young-adult literature.”

Edinburgh Critical Guides to Literature Series: Includes two editions on children’s literature, the latest issued in 2014.

Speaker Series

MacLeod Children’s Literature Lecture Series: “The MacLeod Children’s Literature Lecture Series is a bi-annual program launched by the College in 1999 devoted to exposing scholarly issues associated with children’s literature to a broad audience.”

Lois Lenski Children’s Literature Lecture Series: “The Lois Lenski Children’s Literature Lecture Series was instituted in 1994 to honor children’s author Lois Lenski, who gave so generously of her time and her papers to the students of Illinois State University.”

The 2014 Lowell Lecture Series: Gateway to Reading: “The 2014 Lowell Lecture Series Gateway to Reading explores the fundamental importance of childhood literacy and addresses the joys, discoveries, questions, and challenges facing today’s generation of young readers.”

Scholarly Blogs

The Brown Bookshelf: “The Brown Bookshelf is designed to push awareness of the myriad of African American voices writing for young readers.”

Disability in KidLit: “Disability in Kidlit began as a month-long event in July 2013, featuring daily posts by readers, writers, bloggers, and other people from the YA and MG communities discussing disability and kidlit.”

SDSU Children’s Literature: San Diego State University’s English and Comparative Literature program blog.

Twitter Accounts Maintained by Scholars in the Field

Latin@s in KidLit: “Exploring the world of Latino/a YA, MG, and children’s literature.”

Disability in KidLit: “We review & discuss the portrayal of disabled characters in MG/YA novels.”

Mitali Perkins: Maintains a list of “[t]weets about racial and cultural diversity in the children’s book world.”

Philip Nel: “Professor. One of @TheNiblings4. Two-time Eisner loser. Crockett Johnson & Ruth Krauss, Tales for Little Rebels, Dr. Seuss: American Icon. All views are my own.”

Twitter Accounts Maintained by Institutions Related to the Field

Just Us Books: “Premier Publisher of Black-Interest Books for Children”

Children’s Literature Association: “The Children’s Literature Association (ChLA) is a non-profit association dedicated to the academic study of literature for children.”

Children’s Literature Reviews: “We are an independent review source of Children & YA books & media. CL also assists schools/conferences in hosting author & illustrator events & book sales.”

Racism and the (History of the) Teaching of English Literature

from http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/41xnXzmzpGL._SY344_BO1,204,203,200_.jpg

This discussion of Professing Literature: An Institutional History by Gerald Graff[1] is based on the idea that, as stated by David Gillborn, “the most dangerous form of ‘white supremacy’ is not the obvious and extreme fascistic posturing of small neo-nazi groups, but rather the taken-for-granted routine privileging of white interests that goes unremarked in the political mainstream” (485).[2] This subtle, heightened form of white supremacy can be found easily throughout the history (and contemporary) teaching of English in the United States, yet – disturbingly – in his history of English studies in the U.S. academy, Graff elides and sometimes even excuses this racism.

Graff paints an idealized history in which the field-coverage principle[3] allows for the accommodation of “disruptive” areas such as “contemporary literature, black studies, feminism, Marxism, and deconstruction” without “paralyzing” the whole of the department (7). (Ableist use of dis/ability as a metaphor aside, shouldn’t the goal of these areas and methods of study be precisely to disturb the entire department structurally, rather than to merely be ‘tacked on’ to avoid challenging anyone’s privilege?) He writes that newer (and presumably, according to his analysis, less racist) critics in English will encounter protests from “senior” (and presumably, according to his analysis, more racist) faculty members, but when these people (men) retire, “his replacement [will] most likely [be] somebody who had quietly assimilated the [new] critical methods, with the offensive prejudices smoothed away” (194).

The narrative this creates is one of relentless positivism: it creates a story in which the history of English teaching is shaped by a linear progression of always getting better, always getting less racist, misogynist, etc., simply by the progression of time and the waiting for racist, misogynist, etc., faculty to retire. This is enormously problematic, as is any argument that constructs history as a progressive “it gets better” (Dan Savage? Ick!) narrative.

(“‘The civil rights movement happened, Obama got elected, hooray, let’s all be ‘colorblind’ and postracial!’

‘NO. BECAUSE MASS INCARCERATION THOUGH.’”)

Equally alarmingly, Graff dismisses concerns about the whiteness and maleness and straightness and ableist-ness and middle classness and need-I-go-on-ness of the literary canon. He comforts readers by claiming that, “it was up to each instructor (within increasingly flexible limits) to determine method and ideology without correlation to one another” (9). In other words, a hegemonic canon is fine, because you never know who’s teaching it: you might have an anti-racist professor in there somewhere, and that makes it all better.

from http://www.memecreator.org/static/images/memes/248743.jpg

Oddly enough, Graff acknowledges later that there is a question of “whether the effectiveness of teaching can be fairly measured apart from the institutional forms that shape it” (227). Surely not. Surely an evaluation of all teaching is subject to an evaluation of the institutions in which this teaching occurs. And if this is the case, it is a problem greater than relying on individual teachers to subvert it that the canon is what the canon is, with the occasional obligatory Baldwin and the rarer, partially obligatory Walker tacked on.

Tacking on has been a revolutionary, radical starting point – for example, adding women’s studies programs into English programs, as Graff mentioned above – but that is what it has been: a starting point. We cannot write off the vast history of oppression within English education (and education more broadly) – Who are most of our professors? What texts do we make our students read? What dialect of English do we make them write in? Who has and has had unfettered access to “higher” education, anyway? – by taking permanent solace in a starting point.

from http://carmenkynard.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Screen-shot-2012-02-15-at-1.04.04-PM.png

So what do I propose? That any history of English education in the U.S. examine that history through postcolonial, queer feminist, and critical disability lenses. The results will be more complicated than narrating the debates between white men over the years (which is most of Graff’s book), but such a reading would also be infinitely more rewarding.

————————————————————————————–

[1] Graff, Gerald. Professing Literature: An Institutional History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

[2] Gillborn, David. “Education Policy as an Act of White Supremacy: Whiteness, Critical Race Theory and Education Reform.” Journal of Education Policy 20.4 (2005): 485-505.

[3] This principle states that the prominence of different fields within English departments encourage an expanded breadth of coverage of topics while discouraging interaction between interrelated but discretely listed fields (6-7).