By: Catherine Sara Engh

I’ve annotated sources for two different papers that I’m working on. One is on representations of the frivolous woman of fashion, a social type pictured in James Gillray’s satirical prints and a minor character in Jane Austen’s early novels. The other paper is on trance, negative emotions and acts of first-person narration in Coleridge’s and Wordsworth’s lyric poetry. I’ve listed theoretical sources first, Austen/Gillray sources second and Coleridge/Wordsworth sources last.

Ngai, Sianne. Ugly Feelings. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2005. Print.

Sianne Ngai treats twentieth century art as a privileged location for the exploration of negative feelings. The negative feelings that Ngai identifies–envy, irritation, anxiety, animatedness–emerge where agency is suspended. These feelings are either objectless or ambivalent about their object. Unlike the “vehement passions” of canonical literature–anger, fear, elation–ugly feelings are weak. They do not occur suddenly, but persist over time. Central to Ngai’s argument is her definition of literary ‘tone’ as neither the subjective emotions a text calls up in the reader nor an emotion inside a text that the reader can analyze at a remove, but some combination of both. Ugly feelings manifest where there exists some confusion about the subjective or objective status of a state of being, a confusion that is the basis for that condition of not knowing how one is feeling. Ngai’s project is more theoretical than historical–she does not write a history of ugly feelings. Rather, she lays the groundwork for an approach to literary criticism that may motivate further historical research. Ugly Feelings is a useful source for those interested in bringing the problems of negative feeling to bear on their work.

Brison, Susan. Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of a Self. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2002. Print.

Susan Brison’s book is a first hand account of her experience of rape and its aftermath–the judicial process, the responses of her friends and family, her growing involvement in the activist community and her decision to have a child. Her first-hand account of her “working through” is accompanied by her research in the fields of cultural analysis, feminist criticism, philosophy and neurology. Brison posits that traumatic experience is tantamount to a radical loss of a self. Because Brison sees the self as intersubjective, the telling of one’s story to an audience of sympathetic listeners is essential to the trauma victim’s reconstruction of a self. Telling one’s story helps one regain a sense of control over one’s life. Brison’s first person account practices this essential component of her argument. She understands the self as narrative but also as embodied–because trauma is lodged in the body, it cannot be easily overcome by the mind. Brison situates her book inside a tradition of autobiographical accounts of rape and in relation to the fields of trauma studies, feminist criticism and philosophy. Her book is original for its integration of autobiography with extensive and diverse research. A must-read for feminists interested in issues of gender and embodiment.

Woloch, Alex. The One vs. the Many: Minor Characters and the Space of the Protagonist in the Novel. Princeton UP, 2003. Print.

Alex Woloch intervenes in a debate between literary critics over the interpretation of character. Placed at the intersection of story and discourse, his concepts of character-space and character-system integrate conflicting accounts of character given by structuralists and humanists. With chapters focusing on the novels of Jane Austen, Charles Dickens and Henri de Balzac, Woloch argues that the nineteenth century realist novel is often aware of the disjunction between a minor characters’ implied being and the manifestation of this being in the fictional universe. Woloch claims that the realist novel situates a well-developed central consciousness in an extensive social world inhabited by minor characters and, in doing so, tells us of a social system in which theories of democracy and human rights were maturing as inequality persisted. Woloch’s authority is grounded in the numerous 18th century realist novels he reads–he moves fluidly from Middlemarch to Madame Bovary to In Search of Lost Time–and in the work of relevant theorists–Luckas, Marx, Barthes, Watt, Forster. This book will be of special interest to those interested in narratology and/or realist aesthetics and the 19th century novel.

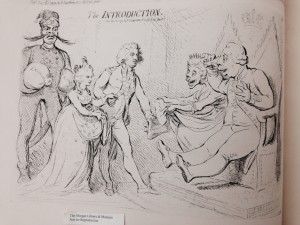

Donald, Diana. The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Age of George III. New Haven: Yale UP, 1996. Print.

Diana Donald’s book gathers British satirical prints produced and sold during the reign of George the III, or, as she says, in the “golden age of caricature.” She argues that the mixed aristocratic, middle-class and working class audience for the prints and the juxtaposition of educated allusion with impolite subject matter in the prints themselves make it difficult to situate the caricature prints of Gillray, Cruikshank, Rowlandson and others as either ‘high’ or ‘low’ art. Donald traces the formal origins of the style developed by caricaturists during this period and her close readings of the prints are materially grounded in the production and distribution processes. This book gathers a vast range of caricatures that are otherwise hard to access and organizes the images in respective chapters on social and political satire. Donald was the first scholar to write a book on this material and her text is a must-see for anyone interested in graphic satire in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Harding, D.W. Regulated Hatred and Other Essays on Jane Austen. Ed. Monica Lawlor. London: Athlone, 1998. Print.

“Regulated Hatred” is the title of a lecture on Jane Austen that the psychologist and literary critic D.W. Harding gave in 1935. “Regulated Hatred” changed the course of Austen criticism by replacing the Victorian’s “gentle Jane”–an authoress who, above all, valued civility–with an Austen who sharply, even mercilessly, criticized the conventions of her society. The collection of essays included here were written over the course of sixty years; some published in Harding’s lifetime, some not. The scope of the book is limited by Harding’s biographical/psychological approach but his observations on the formal qualities of Austen’s novels remain relevant. This book will be valuable to anyone interested in the history of Austen criticism or the formal attributes of her work.

Beer, John. “Coleridge, the Wordsworths, and the State of Trance.” The Wordsworth Circle 8.8 (1977): 121-38. Print.

Beer’s basic claim in this essay is that there was a system behind William Wordsworth’s and S.T. Coleridge’s usage of the term “trance.” Beer focuses, for the most part, on the early poetry of Wordsworth and Coleridge–the Lyrical Ballads, The Prelude and Coleridge’s conversation poems. But he also incorporates material from the journals of Dorothy and the notebooks and letters of Coleridge. Drawing on the etymology of the word “trance,” Beer proposes that, in Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s poetics, the word may refer to the noun “entrance”–a passage of some kind–and to the verb “entrance”–a transport of feeling. Also important is the affiliation of trance with death, a signification that will later be picked up by Keats. Through close readings, Beer argues that as Wordsworth and Coleridge became disenchanted in personal relationships, the social and sexual implications of the term were de-emphasized and trance was associated with childhood and the psychological extremes of calm and agitation. The absence of contemporary “theory”–much of which hadn’t been written in 1977–and the emphasis on close readings of verse and prose make for an essay remarkably different in approach to what is now published in the same journal.

Berkeley, Richard. Coleridge and the Crisis of Reason. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Print.

Richard Berkeley critiques Thomas McFarland’s analysis of Coleridge’s encounters with German philosophy in Coleridge and the Pantheist Tradition (1969). McFarland sees Coleridge’s interpretive dilemma as one between two ways of doing philosophy–philosophical inquiry as originating with the phrase ‘I am’ (rationalism, Jacobi) or ‘it is,’ (pantheism, Spinoza). Berkeley sees this as too simple an approach to the problem, one that distorts the philosophy of Spinoza and Jacobi and the controversy over pantheism that Coleridge would have been familiar with. In Berkeley’s view, the pantheism controversy orbited around the status of reason in Spinoza’s philosophy. Coleridge was not wrestling with two ways of doing philosophy, as McFarland claims, but with conflicting ways of interpreting Spinoza. In Chapter one, Silence and the Pantheistic Sublime in Coleridge’s Early Poetry Berkeley argues that Coleridge’s early conversation poems–“the Eolian Harp,” “On Leaving a Place of Retirement”–articulate a tension between reason and faith that was at the heart of the pantheism controversy. Berkley shifts the conversation about Coleridge and pantheism from one about influences to one about anxieties over the status of reason. This book intervenes in a very specific area of Coleridge studies and will be of interest to anyone working on Coleridge or Spinoza.

Larkin, Peter. “‘Frost at Midnight’–Some Coleridgean Intertwinings” The Journal of the Friends of Coleridge 26. (2005): 22-36. Web. <http://www.friendsofcoleridge.com/Coleridge-Bulletin.html>.

Larkin generates a phenomenological reading of Coleridge’s 1798 conversation poem ‘Frost at Midnight.’ Drawing on the work of Avatal Ronnell, Larkin compares a good reading of a beautiful poem to a greeting–rather than overwhelming a poem with our learning, we should allow our experience of the poem to enable us to ask new questions, to bring what we know into conversation with the poem. What emerges is not a finalized and definitive explication, but a precarious questioning process. The structure of Larkin’s essay enacts this ‘greeting.’ He reads ‘Frost at Midnight’ and then considers the affinities between Coleridge’s thought and the claims of phenomenology. He applies the work of Merleau-Ponty in The Visible and the Invisible to ‘Frost at Midnight,’ finding phenomenological reversals–or intertwinings–between a perceiving subject and its object in ‘Frost at Midnight.’ Central to his reading is the idea that the subject–Coleridge–perceives in objects the forms of transcendence but that something of the object world remains hidden and inaccessible. Larkin’s authority derives from his knowledge of philosophical concepts and contexts–the influences and precedents to Coleridge’s and Merleau-Ponty’s thought. He speaks fluently about Coleridge’s concept of the primary and secondary imagination and Merleau-Ponty’s notion of ‘the flesh.’ Much Coleridge criticism that I have come across–books like Berkeley’s Coleridge and the Crisis of Reason and Ramonda Modiano’s Coleridge and the Concept of Nature–limit the extrinsic material they bring to bear on Coleridge’s writing to work written in or before Coleridge’s time. Larkin’s application of more contemporary claims of phenomenology to Coleridge’s work is refreshing.

Fulford, Tim. Landscape, Liberty and Authority. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996. Print.

In Landscape, Liberty and Authority, Tim Fulford takes a new historicist approach to the poetry and prose of Thompson, Cowper, Gilpin, Coleridge and Wordsworth. Landscape, Liberty and Authority is concerned with ‘discourses on landscape’–literary representations of nature but also writing that uses the motifs of landscape description to make critical and political arguments. The poets and writers Fulford discusses ground their authority in the landscape, which emerges as a site where power struggles, particularly over the status of gentlemanly taste, erupt. Fulford maintains that Coleridge and Wordsworth were the first to explicitly attack the aesthetic and political values of the gentleman. However, these romantic poets, like Thompson and Cowper before them, maintained a vexed relationship to a readership that still espoused many of the values they were criticizing. Fulford brings an extensive knowledge of political contexts–party politics, the politics of enclosure and the French Revolution–to bear on his readings. He is great at working through ideological nuances, uncovering influences and explaining how these writer’s social/political stances differed from those of writers who came before them.

Ann, Bermingham. “The Picturesque Decade.” Landscape and Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition 1740-1860. Berkeley: U of California, 1986. Print.

Ann Bermingham conducts an Althusserian reading of English landscape paintings from 1740-1860, focusing on the landscapes of Gainsborough, John Constable, the picturesque painters and the Pre-Raphaelites. Bermingham stages Landscape and Ideology as an intervention in a field of art history that, in 1986, typically situated landscape painting in a familiar history of stylistic development. Traditional approaches problematically assume historical neutrality. In contrast, Bermingham believes that there exists a relationship between landscape paintings and the dominant social and economic values of a time when the growth of industrial capitalism was changing the socio-economic order in the English countryside. In chapter two, “The Picturesque Decade,” Bermingham discusses the social anxieties of Knight and Price–gentlemen whose system of landscape gardening privileged rusticity and an appearance of wildness. She elaborates the paradox of a situation in which the very men who were enclosing the land were building gardens that nostalgically returned to a time before the land was enclosed. Since Landscape and Ideology was published, ideological approaches to landscape have become more common–Fulford’s book is a good example of a similar approach applied to representations of landscape in poetry.

Sources in French

Gould, A. (1975). The English Political Print, From Hogarth to Cruikshank. Revue de L’Art (France), (30), 39-50, 98-101. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1320614744?accountid=7287

Focusing on stylistic development, this article traces a history of the British political print and engraving, starting with Hogarth and ending with Rowlandson and Cruikshank. Gould argues that Gillray paved the way for the political cartoon, placing him at odds with Diana Donald. While Donald emphasizes Gillray’s importance, she situates him at the latter end of the heyday (1760-1820) of political caricatures in England. For Donald, Gillray was a particularly well-educated and skilled innovator of the form, but one who was nonetheless influenced by cartoonists who came before him. Gould, as is now common, starts his discussion of political prints with Hogarth. This article came before Diana Donald’s book and demonstrates that scholarly work was being done in France on this medium before the 90s.

Emma Eldelin, “Exploring the Myth of the Proper Writer: Jenny Diski, Montaigne and Coleridge”, TRANS- [En ligne], 15 (2013). Web. <http://trans.revues.org/751>

This essay explores the relationship between the British author Jenny Diski’s On Trying to Keep Still (2006) and two epigraphs that frame this book. One is from Coleridge’s poem ‘This Lime Tree Bower my Prison’ and one is from Montaigne’s Essays. Eldelin is interested in how the epigraphs integrate Diski’s book in a literary tradition, comment on the text and mark her genre. She sees both epigraphs as enunciations related to the plight of the solitary writer and explores what it means to bring the voices of old texts to bear on a contemporary piece of writing. This article is unique in its focus on epigraphs and in its movement across periods and genres. Research-wise, I suspect this essay would not be considered rigorous enough to be published in a journal like Studies in Romanticism or The Wordsworth Circle.