By: Austin Bailey

My Reading Desk.

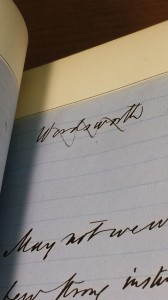

For this assignment I made use of Michael’s wonderful suggestion to check out Archive Grid: http://beta.worldcat.org/archivegrid/. I found this to be surprisingly easy to use and quite helpful. You type in search criteria and it pulls up a list of libraries that carry matching items. This led me to the Morgan Library. My search criteria was “Ralph Waldo Emerson.” It turns out the Detroit Public Library has most of his papers and there are other items scattered across New England and California. However, I found two items of interest at the Morgan Library: a collection of newspaper and journal clippings relating to the transcendentalists and hand written notes from a 1859 speech Emerson delivered on behalf of John Brown. This speech was delivered on November 18th, roughly a month before John Brown was hung for treason. Below is a photograph.

Emerson crosses out “Wordsworth.”

Emerson crosses out “Wordsworth.”

I thought this was neat because it’s the word “Wordsworth” written then crossed out. It seemed to have resonance by itself, floating atop the page and seemingly separate from the rest of the text. It reminded me of a comment I read recently in Harold Bloom’s 2012 Anatomy of Influence: “A great poet in prose, and a very good one in verse, [Emerson] invested himself in his journals, lectures, and essays because Wordsworth’s giant form blocked the New England seer from achieving a full voice in verse” (209). It’s interesting to think in terms of how the archive can inform and dialogue with our preestablished critical frameworks. Putting this next to Bloom’s assertion, for example–an assertion that seems generally true, so in a sense hard to assess–we can think about how process works in the making of a text. This would suggest a different way of thinking about influence, seeing it as more palimpsestic and usable rather than anxious and oppositional. (I don’t particularly buy what Bloom is saying anyway. Emerson wasn’t the best poet because he sounded too Victorian despite his desire not to. This wasn’t due so much to an anxiety of influence as it was to his inability to get his pitch right in verse. He knew this himself and remarked once that his voice was a “husky” one, better suited to prose.)

I was kind of surprised by how formal the archive was. It was like meeting a celebrity or going through airport security (though much more aesthetically pleasing). Catherine mentioned the Morgan Library’s archive system in her post but I’ll iterate my own version here. You can’t get to the Morgan Library’s reading room directly; you have to be escorted there. A nice man with a pony tail helped me get my visitor’s pass and took me upstairs to it.

When you get to the reading room you are instructed to put your personal items in a storage locker and to wash your hands. You present your ID to the archivist behind the glass. Then they let you in. It’s all very procedural. They instruct you to read through a list of rules and handling instructions. While you’re doing this they prepare the requested materials for you. In my case, these were newspaper clippings in a bound book, one that I could touch freely as they were simply xerox copies. But the other item I requested–the hand-written Emerson speech–was in a bound book placed on a kind of reading dais (I’m not sure what the exact term for it is but it’s essentially a wooden book holder). For these types of items you’re allowed to move the pages (carefully of course) but you are instructed not to reposition the book in any way. Below is a photo of the entrance which I surreptitiously snapped.

There was one other person doing research. He was photographing some series of illuminated manuscripts. There was an odd moment when one of the archive curators said to the other one: “Want me to move this stack of books so you can see him better?” referring to the researcher who was observing the illuminated manuscripts. The researcher then cheekily responded: “You can’t see me Marie?” with a smile. He and the archivist knew each other well enough to be on a first-name basis (at least in his mind) yet the curator was talking audibly about surveiling him. The whole scenario seemed oddly interesting.

As cliche as it may sound, there was something wonderful about being in the presence of all that literary historical material. I have no investment in manuscript studies per se, but I found myself wanting to trade with the guy next to me–his materials for mine–just so I could have a different viewing experience. Part of what was so alluring about Emerson’s script was that it looked like something someone could’ve written yesterday, as it was only black ink scribbled on blue-lined legal paper. It made me recall our conversation with Steve Jones and what he said about the delicacy of more recent textual materials, since they were printed on cheap, acidic paper.

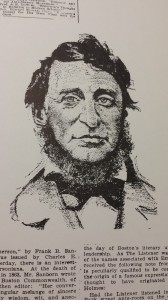

Sketch of Henry David Thoreau, from the transcendentalist notebook.

Sketch of Henry David Thoreau, from the transcendentalist notebook.

I think being in the presence of the archive had an impact on me in two key ways: 1) it opened me up to an area of scholarship which I have heard a lot about but have not had any direct experience with, that being archive work in general, and 2) it made me aware of one of the salient values of the archive, which is to put the scholar in contact with the corporal presence of the text in its initial makings. This generates a new-found sense of a text being something that is made. It puts one in touch with the materiality of thinking and its affective forces. While none of the materials I found are directly relevant to what I’m working on now, I did snap some photos of some important journal clippings. These journal clippings presented in aggregate a record of Emersonian critical reception in the last years of his life and right after. Interestingly, what they reveal is that a lot of the conversations talking place within academe in the late 19th century concerning the meaning of Emerson’s work are surprisingly similar to one’s taking place now. Of course, certain elements of the 19the century conversation are dated and very different; still, there are skeletal similarities in the ways these late 19th century American and European literary critics themetized his oeuvre. I have made note of these things as they will come in handy in the future.